Hello, Future. Through an Urbanist’s Lens

BY KELVIN OBURI

At the time of writing this article, it’s still 2025. The new year is approaching quickly, and with it comes that familiar urge to pause and reflect. I find myself wondering what the next 10, 20, or even 100 years might look like. It’s strange to think that COVID was only six years ago. In many ways, it feels much closer. In others, it feels like a different era entirely.

A lot has changed since then. Life, at least in the parts of the world I know, seems to move faster every year at an unprecedented pace. Up until 2022, generative AI was still largely a concept. Today, it’s woven into daily routines, especially for younger people, educated people, and higher-income workers in office and knowledge-based jobs. Whether we celebrate this shift or feel uneasy about it, the speed of change is undeniable.

This reflection isn’t meant to predict the future or to sound alarmist. It’s simply an invitation to pause and consider how far we’ve come as a society and where we might be headed next.IMAGE CREDIT: STUDIO MUTI - FOLIO ART

Cities, after all, have never been static. Since the 1940s, urban areas across the United States have undergone enormous transformations. Postwar policies, technological inventions, and industrial growth reshaped neighborhoods, transportation systems, and daily life in ways that still define our cities today. If cities were able to change so dramatically in the past, what would prevent equally significant transformations over the next century? Will we ever witness a Haussmann-like overhaul of a modern-day city?

Many of us reading these words may never experience the full outcomes of the decisions being made today. But we are living in the period when those decisions are taking shape. Whether we realize it or not, we are participants in the long-term experiment of city building.

As technology continues to accelerate and reshape how we live and work, it becomes increasingly important to consider the social fabric of our cities. We are more digitally connected than ever, yet nearly 60 percent of young adults are experiencing a loneliness epidemic. Yes, New Urbanism alone cannot solve loneliness, but its core ideas align closely with what research shows humans need to feel less isolated. When paired with thoughtful social programs, these principles can make it easier for people to meet one another, build relationships, and develop a sense of belonging that no app can replicate.IMAGE CREDIT: SHIFT IN PLAYING FIELD - RANGANATH KRISHNAMANI

Urban form plays a quiet but powerful role in this. Housing located near shops, cafés, and parks, connected by walkable street networks, creates opportunities for chance encounters. Public spaces that invite people to linger—small plazas, shaded benches, and edges people can sit on—encourage everyday interaction. Even subtle design elements matter. The presence of children at play often makes a space feel naturally vibrant and peaceful. Art, sculpture, and small moments of beauty can slow people down just long enough to notice one another.

There is also value in scaling down and distributing daily services across communities. When retail, amenities, and workplaces are spread throughout a city rather than concentrated in isolated districts, everyday life becomes more social by default. Instead of working exclusively from home, decentralized work hubs can offer spaces where smaller teams gather locally while still remaining connected through technology. Innovation does not disappear when people meet in person—it often deepens.IMAGE CREDIT: ENVISIONING POST-PANDEMIC PRACTICE - GAUTAM & GAUTAM ASSOCIATES

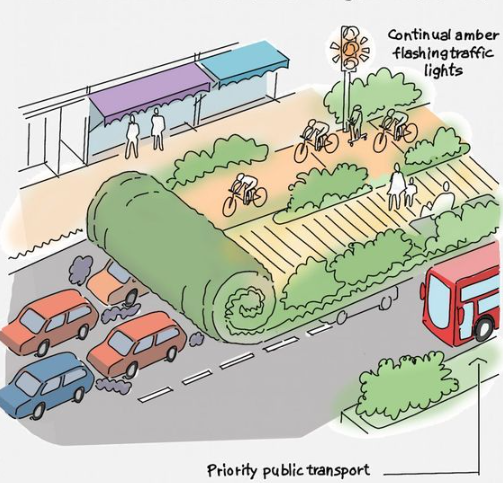

Throughout history, different inventions have changed how people move from place to place. Horses gave way to streetcars, which gave way to automobiles, and now to emerging technologies we are only beginning to imagine, like robotaxis and flying cars. Yet the most basic form of movement has remained the same: walking. I doubt that will change anytime soon.

This is where the principles of New Urbanism matter most. Walkable neighborhoods, mixed-use places, and well-defined public spaces are not just aesthetic preferences. They function as social infrastructure. They create opportunities for routine interactions, chance encounters, and everyday connections.

In much of the United States, walking is often treated as secondary. Long distances, disconnected street networks, and single-use zoning make daily walking impractical or unsafe.

Over time, this erodes community life and reinforces isolation, even in places full of people. Walking is more than transportation. It supports physical health and mental well-being. It allows children to explore, older adults to remain engaged in the community, and neighbors to recognize one another. Cities that fail pedestrians often fail their inhabitants in quieter, more insidious ways.

Perhaps if urban areas did not separate the very facets that build community—where people live, work, shop, and play—people would feel more connected. The widespread separation of these functions has ignored human scale and everyday rhythms at a biological level. For many readers, this is the only urban pattern we have ever known. We did not experience cities shaped by the pace of walking or the logic of proximity. But that does not make our current model inevitable or permanent.image credit: crockerpark.com

The future of cities is not an illusive dream or an abstract concept waiting to arrive. It is already under construction. It is tempting to focus on technology and spectacle, but the quieter decisions—how we design streets, neighborhoods, and public spaces—matter far more than we often realize. In many ways, this reflects the Pareto principle: a small number of decisions shape a disproportionate share of outcomes.

When citizens in the future celebrate the turn of a new millennium, will they pause to appreciate the choices their ancestors made in 2026?AUTHOR BIO:

Kelvin Oburi is an architecture student at Andrews University in Berrien Springs, Michigan. He is passionate about walkable, human-centered communities and New Urbanism. He is involved in student leadership and design advocacy and will serve as the 2026 CNU Midwest Student Board Representative, representing student voices and perspectives across the region.